Related

SUISEKI AESTHETICS

Suiseki Aesthetics

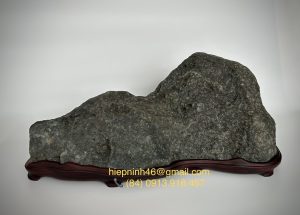

SHAPE

The Japanese have developed a detailed classification system that helps field collectors assess their found treasures. These classifications help in the visualization process. All suiseki must have a recognizable shape that is suggestive of mountains, waterfalls, canyons, cliffs, etc. Human forms and animal forms are other valued shapes. Lastly, for those that do not fit the many recognizable classifications, there is an abstract shapes category called chusho-seki. Shapes best identified in the stones profile. Classifications must fit into a Golden ratio design. There should be a one-third, two-thirds composition, horizontally or vertically. Of course these rules may be broken, but there better be good reasons for it in terms of what other attributes suiseki possess.

TEXTURE

Textures may be smooth or rugged, and should be in harmony with the suiseki. Textures create the lakes, glaciers and fields of flowers on a suiseki. The heavily textured suiseki, or hadame, is highly prized. The more textural variety on a suiseki the more aesthetic value it has.

COLOR

Color helps create the power of suggestion in suiseki. Although many collectors search for the elusive black or kuro stone, in truth they are not that common. The research for my book showed that 68.5% of Japanese suiseki are shades of gray, and only 18% were black. Collectors should not shy away from collecting what is available in their countries. Although we in Northern California are blessed with a plethora of minerals in all colors, not all countries have such a geological cornucopia. Nevertheless, I believe suiseki artists should be proud of what they can find in their back yards, and not be defensive about the fact that their stones are light in color or consist of soft minerals. If the stones meet other criteria — especially shape — then the collector has a potential suiseki. To simply purchase foreign stones just because they are black does a disservice to the art in collectors home countries.

PATINA

A stones sheen or luster develops over time. Nature does its share, then its up to the owner to handle it often, rubbing it as much as possible. The harder the mineral: jadeite, nephrite, serpentine, jasper, etc., the easier it will be to enhance its patina. Keep in mind that rough-textured suiseki do not have patina, and it should not be forced on it it will look artificial. Patina may be equated to the sheen on beautiful antique furniture. The harder the mineral the better the patina. Minerals with a Mohs mineral scale hardness of at least 5 is recommended.

Harmony & Balance

Quality suiseki have a sense of unity that is obvious to the eyes. They should have visual tension, yet also have a sense of solidity, of place. A suiseki must sit securely in its daiza, not look like its going to topple over or sit in a daiza too big for its base. The stones color, texture, patina and shape should meld into a wonderful statement of the art that captivates the eye.

WABI SABI

Embracing all the attributers discussed above is the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi. Wabi-sabi may be best defined as a religious and philosophical aesthetic that helps shape our way of experiencing the unique qualities of suiseki. Wabi-sabi, developed in the sixteenth century under the influence of Zen Buddhism, evolved into a standard of beauty that emphasizes imperfection, incompleteness, and ordinariness. In wabi-sabi, the natural environment becomes a medium through which personal truth and spirituality can be explored. The melancholia associated with distant, lonely places is a type of wabi-sabi. Similarly, the field collector sees in the banal and often overlooked details of a stone a world of emotional recollection. It values the differences and imperfections that make objects one of a kind, and it is comfortable with the fundamental unpredictability of nature. It emphasizes the organic universe (growth, decay, erosion, etc.), soft and vague shapes, and attrition over time. It seeks to expand sensory information, and it tolerates ambiguity and contradiction. In tone, wabi-sabi is dark and dim. Wabi-sabi in suiseki emphasizes yugen, or the sudden perception of something mysterious and strange, hinting at an unknown never to be discovered shibui, anything reserved, refines, quietude, and, aware, when the moment evokes a more intense, nostalgic sadness, connected with autumn and the vanishing world. I have translated concepts of wabi-sabi into a suiseki aesthetic that includes, but is not limited to the following: suiseki as a natural, changing, dynamic, odd over even, suiseki as the personal, the mundane, and suiseki as the ultimate statement about simplicity.

SHIBUI

Shibui, simply stated, means the representation of the art object (in our case), in a low-keyed manner. There is no ostentatiousness, no garishness. Suiban should not be bright in color, for example. The daiza should not consist of woods that are bold and call too much attention to themselves, like oak with its pronounced grain. Also, the wood should be satin in finish, not glossy, and not be crafted in an ugly, non-professional manner.

Source from Suiseki – The Japan art of Miniature Landscape Stone, P. 63 – FELIX G. RIVERA